Modern Medicine and Dispensable Female Body Parts

Expressing unease with the celebration of Angelina Jolie’s double mastectomy, this article argues that the medical industry has played a masterstroke by casting the mastectomy debate in terms of an older “rights discourse” of the women’s movement. It suggests that the feminist and progressive movement hit back by asking questions to the scientific establishment about access, costs, and the necessity of specific forms of treatment. That may be the way forward towards not only accountability to “consumers”, but actually for equitable health-care for all.

G Arunima (arunima.gopinath@gmail.com) is with the Centre for Women’s Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

In this last week, social media, blogs, websites, and news sites have been awash with reports, and opinions, about Angelina Jolie’s preventive mastectomy. Apparently falling in a genetically high risk category, she chose this procedure for both breasts, so that she would be there “for [her] children”. She, as the tagline goes, chose life over cancer. Mostly enthusiastic, reports are also describing this as something “brave”, applauding her for “coming out” about this, in order to help other women.

Consuming Health

So I ask myself – why am I not responding to this with the requisite amount of enthusiasm, indeed euphoria, that seems to be accompanying the media coup of the week. In part, this is to do with an instinctive mistrust of the manner in which modern technology in the last few decades has invaded and displaced all other forms of medical care, creating simultaneously a kind of pseudo scientific common sense.

The Jolie case itself reveals many elements of this. For instance, the liberal references to percentages, without ever clarifying sample sizes, racial or national contexts, or age profiles, is a classic instance of the misuse of statistics. Most reports mention hitherto unheard of genes (except presumably in medical circles) and within a mere forty eight hours or so the BRCA gene has achieved a resounding degree of notoriety. The combination of math and science in this fashion, needless to say, is a noxious cocktail. And as marketing strategy, not entirely unfamiliar.

Indeed, the steady shift to technological interventions, and medical procedures involving multiple levels of assessments (“tests”) has been undergirded by what can be termed as the ‘genetic turn’ in popular scientific discourse. As someone untrained in any kind of science, medical or otherwise, it would not be my place to mount a critique of developments in the field. However, having been reduced to being a “consumer”, like millions of others, my response to these trends is primarily one of bewilderment, accompanied by mistrust of a medical system that’s clearly making huge profits whilst subtly introducing anxieties about possible health risks that one might embody, utterly unbeknownst to oneself.

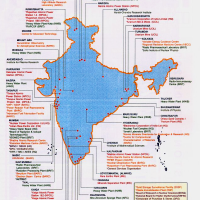

Living in a country with practically no public, or affordable, health care, the growth of the medical industry and new accompanying technologies holds frightening prospects. Other than the fact that the emerging “super specialty” hospitals price the average Indian out, it also successfully instils in everyone’s minds that this is the only form of health care that could provide medical solutions. In an almost caricatured version of neoclassical economic logic of supply creating demand, the profusion of technologies has resulted in a mindless multiplication of tests, where a body becomes the sum of its test results. In this light, the case of women’s health, and bodies, becomes particularly relevant.

The Economy of Predictive Interventions

A frightening dimension of this is the manner in which women’s health has so easily been reduced to reproductive health. In part a UN inspired move, it has, certainly from the 1990s been accompanied by large amounts of focused funding and the emergence of a cottage industry apparently generating research in this area. Two correlates of this phenomenon – albeit leading in opposite directions – have been huge money spinners. One is the increasing medical common sense of preventive intervention in the form of hysterectomies; the other has been in the area of assisted reproductive technologies. Here I want to dwell briefly on the hysterectomy, and what this trend signifies.

Purely impressionistically speaking (and this is an area in which detailed, and reliable statistics would be very welcome) hysterectomies have been increasing at an alarming pace in this country. In states like Kerala, women are routinely advised to remove their uterus, sometimes ovaries, after about 40. The assumption here is that a woman who’s had her children, or past “reproductive” age, doesn’t require this organ. The justification is normally provided on the basis of the existence of uterine fibroids, which could, within this new language of science as dire prediction, eventually lead to malignancy.1

Needless to say, other than the costs and fear that accompany such procedures, most women are also not advised about the short or long term after effects that such surgery could have. The idea of woman as reproductive vessel – with use value during menstruating years – is at least as old as organised religion. Yet there is something else that appears to be happening at this moment of (reproductive) organ dispensability. It is about the manner in which medical discourses are inflected by industry concerns, in which the fear that is generated reaps fine dividends. It is therefore quite educative to see the nascent preventive mastectomy industry emerging, complete with its gene patenting, testing and surgical costs.2

The Gaze on the Breast

In possibly what was one of the earliest feminist reflections on mastectomy, the poet Audre Lorde wrote movingly of her experience in Cancer Journals.3 Far more than Angelina Jolie’s highly publicised “brave” disclosure, Lorde’s quiet voice had powerfully engaged both the trauma of fighting cancer, the then prevalent surgical interventions, and the ‘solutions’ that were on offer. Going to the heart of the economy, and gender politics, of the mastectomy industry Lorde, rejecting prosthetic solutions, asked why “looking normal” would help any woman heal? How unlike Jolie, who has probably given millions to her plastic surgeon for “reconstructive surgery”,4 and has been selected poster girl for the medical industry. This then brings me to the last set of issues I wish to raise here – about the woman’s body, its parts, and the contemporary moment in “disease management”.

In her insightful, and racy, A History of the Breast, Marilyn Yalom rightly points to the need to read the breast not merely as unmediated biological fact, but also as a site of multiple discourses.5 She tracks the manner in which the biological or nurturant function of the breast has been inflected by the erotic, as indeed the scientific and medical. Posed perilously at the intersection of differing, and often competing, attention the breast has constantly evoked desires, fears, and fantasies.

The breast, unlike the uterus (which too has been the produced via multiple discourses) has increasingly been fetishised as a potent, and complex, sign of a woman’s beauty. This has led to its being subject to intensive commercial onslaughts, from the corset industry, silicon implants, to nipple piercings. It looms large in both ideas of motherhood and in pornographic representation. Predictably, such excessive attention to particular body parts, and its place in producing ideal womanhood (reproductive and sexy) has led to a certain kind of feminist unease with women’s bodies.

Often when some feminists speak of throwing away their uteruses or breasts, they are rejecting the tyranny, and consequences, of such an overdetermined gaze on particular female organs. Yet frighteningly, the market savvy medical industry feeds off precisely such views, and produces new regimes of health care that will deliver, rather cold bloodedly, precisely such results at prohibitive costs. Not only that, it also produces an apparently apolitical “scientific” rationale for its marketing strategy.

What is Normal?

Needless to say, this trend of preventive surgical science coexists quite comfortably with heteronormative and patriarchal ideas about women, their bodies, and sexuality in general. Writing of the complexity of trans lives, the historian Afsaneh Najmabadi’s nuanced discussion of the Iranian context maps how sex change surgeries are framed within the utterly objectionable language of “curing” abnormality and deviance.6 Similarly, trans artist James Cameron’s work, with great irony and power, unmasks ideas, and desires, that undergird dominant notions of masculinity. His triptych “God’s Will” where he parodies body builders, using props of syringes, knives and light bulbs, also constantly references the body as ‘performance’ and its being reconstituted continually through acts of self-fashioning.7

I think it is extremely urgent that we engage, and utilise profitably the insights gained from trans experience, with its critique of “normal” bodies, sexuality, and indeed patriarchy. Yes, women must take charge of their bodies and selves. Yet this cannot happen in the absence of a demand for greater accountability and transparency from the medical scientific empire whose solutions are invariably industry driven.

Genetic focus, and folding back into specific women, and their personal histories, needs to be offset by a wider understanding of growing numbers of new cancers, often in people with no identifiable genetic disposition. In other words, its time that we demand that governments, and the medical establishment, invest money and research in understanding the relationship between food, lifestyle, environment and changing global health trends. Can this happen without rethinking development, economy and the very nature of the political process?

Casting the mastectomy debate in terms of an older ‘rights discourse’ of the women’s movement is a masterstroke by the medical industry. I would suggest we hit back by asking feminist inspired questions to the scientific establishment about access, costs, and the necessity of specific forms of treatment. That may be the way forward towards not only accountability to ‘consumers’, but actually for equitable health-care for all.

References

1.Many oncologists, and researchers, would now agree that myomectomy is a far cheaper, and easier, way of dealing with uterine fibroids. This, however, is rarely suggested to patients by the medical establishment. Nor does it engage productively the completely foolproof natural health care regimes that have proven histories of fibroid management.

2. http://jezebel.com/angelinas-cancer-gene-is-actually-patented-by-a-compa…

3. Audre Lorde,(1980) Cancer Journals, Aunt Lute Books.

4. “Angelina Jolie’s story boosts awareness of breast reconstruction, local plastic surgeon says” The Record.com, 17 May, 2013.

5. Marilyn Yalom, A History of the Breast.

6. Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Transing and Transpassing across Sex-Gender Walls in Iran”, WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 36:3 & 4,(Fall/Winter 2008).

7. Melanie Taylor, “Peter(A Young English Girl): Visualizing Transgender Masculinities”, Camera Obscura, 56, Volume 19, No. 2.